The Saga Pattern for Distributed Transactions in Microservices

Saga Pattern: The Secret Behind Reliable Microservices

The Inevitable Challenge of Distributed Transactions

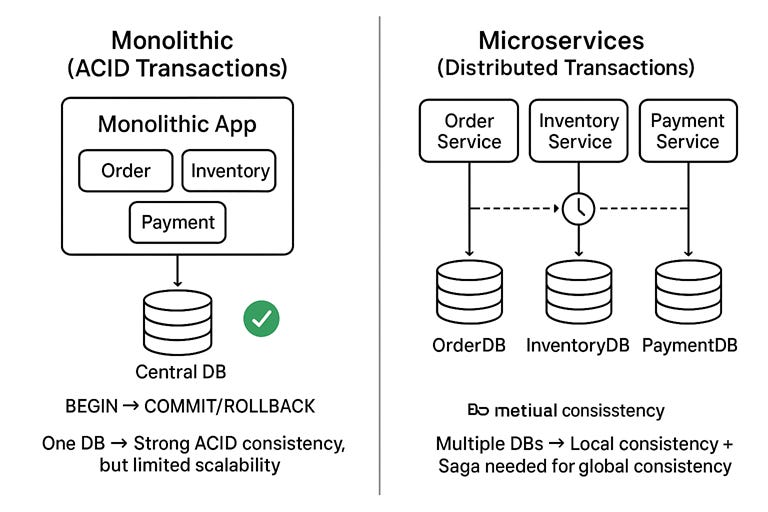

When we moved from monoliths to microservices, we traded one big database for many smaller, independent ones. This shift brought freedom — teams could scale independently, pick the best-fit database for their service, and isolate failures without taking down the entire system.

But freedom isn’t free. Once you embrace “database-per-service”, you hit a brick wall: how do you keep data consistent across multiple services without a central transaction manager?

Think of an e-commerce order:

The Order Service creates the order.

The Inventory Service checks stock.

The Payment Service charges the customer.

Each has its own database, and there’s no single, all-powerful transaction to wrap them together. If one piece fails midway, what happens? Half-complete orders, inconsistent states, angry customers.

This is the heart of the distributed transaction problem.

Why ACID Doesn’t Scale in the Cloud

For decades, we leaned on the ACID guarantees of relational databases:

Atomicity: all or nothing.

Consistency: valid state before and after.

Isolation: no transaction messes with another.

Durability: once committed, it stays.

In a monolith, these rules were sacred and enforceable. In microservices? Not so much.

The network — with its latency, failures, and partitions — makes global ACID guarantees impossible. You can’t “lock” multiple services across a distributed environment and expect everything to just work.

So, we need a new playbook.

Why Two-Phase Commit (2PC) Doesn’t Work Here

At first glance, you might think: “Wait, don’t we already have a solution? What about Two-Phase Commit (2PC)?”

Here’s the short version: 2PC and microservices don’t get along.

2PC uses a transaction coordinator to run:

Prepare phase – ask all participants if they’re ready.

Commit phase – if everyone agrees, lock and commit.

Sounds fine in theory. But in practice?

Blocking problem: Services must hold locks while waiting. Scalability nosedives.

Single point of failure: If the coordinator crashes, everyone’s left hanging.

High latency: Network roundtrips slow everything down.

CAP theorem conflict: Microservices value Availability and Partition Tolerance, while 2PC clings to strict Consistency.

In short, 2PC brings the worst of both worlds: fragile coordination, bottlenecks, and poor fault tolerance. It’s like trying to run a Formula 1 car on city roads — technically possible, but painful and impractical.

The Saga Pattern: A Paradigm for Eventual Consistency

Defining the Saga Pattern

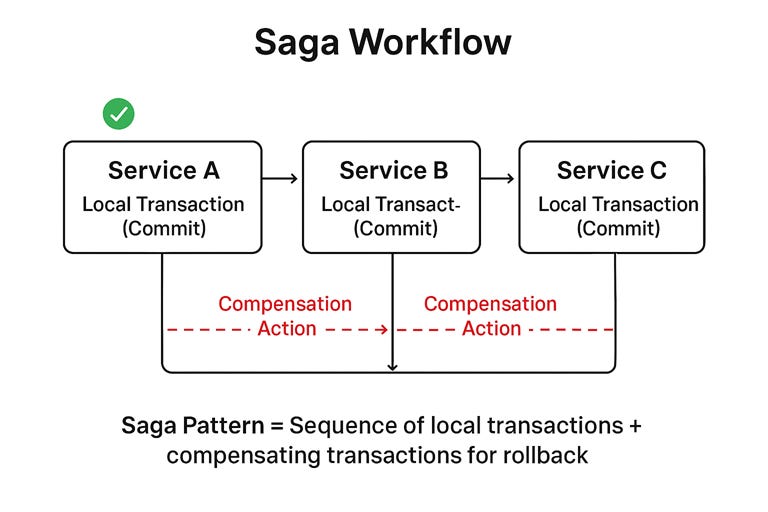

The Saga pattern solves the distributed transaction challenge by replacing the rigid “all-or-nothing” approach of 2PC with a more flexible, stepwise workflow.

A saga is:

A sequence of local transactions — each one runs inside a single service and commits to its own database.

Each step triggers the next through an event or command.

If something breaks mid-way, the system doesn’t just hang — it runs compensating transactions to undo prior steps.

In short, a saga guarantees that your system ends up in a consistent state, but not instantly — it’s eventual consistency rather than immediate atomicity.

💡 Architect’s Tip: Think of a saga as a relay race: each runner (service) hands the baton (event) to the next. If one runner stumbles, the coach (compensating transaction) tells the previous runners to walk back to the starting point.

Compensating Transactions: The Backbone of Sagas

This is where sagas diverge most from traditional transactions.

In ACID, rollbacks are automatic. In sagas, you write the compensating logic yourself.

Example:

A flight booking reserves a seat.

Payment fails.

The compensating transaction un-reserves the seat.

This requires developers to explicitly design undo operations for every compensable step. You’re no longer relying on a magic database rollback — you’re embedding business-aware compensation into your workflow.

💡 Developer Insight: Don’t underestimate compensations. They’re easy when undoing a database row insert, but much harder for side effects like sending an email, pushing a notification, or calling an external API. Design your saga with these realities in mind.

The Life Cycle of a Saga

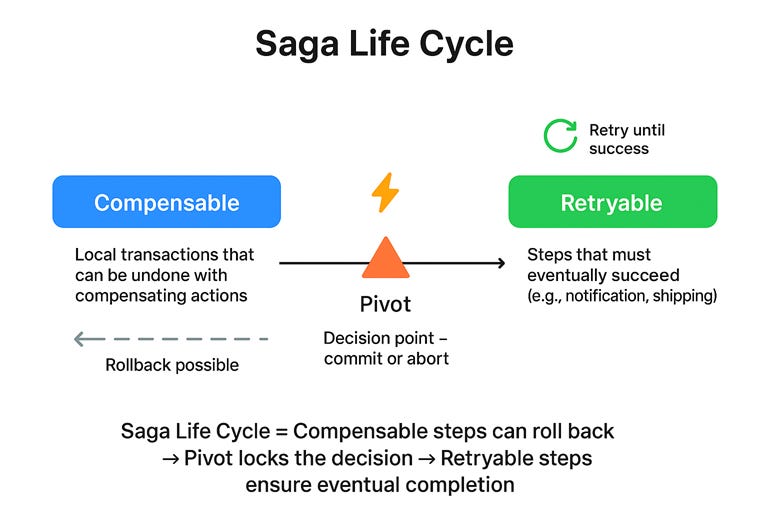

Not all steps in a saga are equal. To handle real-world workflows, sagas classify transactions into three types:

Compensable Transactions

Can be undone if needed.

Example: reserve stock, reserve a seat.

Pivot Transaction (Point of No Return)

Once this step succeeds, there’s no turning back.

The system commits to completion, even if later steps fail.

Example: charging a credit card.

Retryable Transactions

Come after the pivot.

Must be idempotent (safe to retry).

Example: sending an invoice email, updating analytics.

💡 Architect’s Insight:

The placement of the pivot transaction is a strategic decision. Put irreversible actions after the pivot so that failures don’t leave your system in an unrecoverable mess.

Architectural Strategies for Saga Implementation

The Saga pattern isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. You’ve got two main ways to coordinate sagas: Choreography and Orchestration. Both solve the distributed transaction problem, but each comes with its own trade-offs. Choosing between them is a fundamental architectural decision.

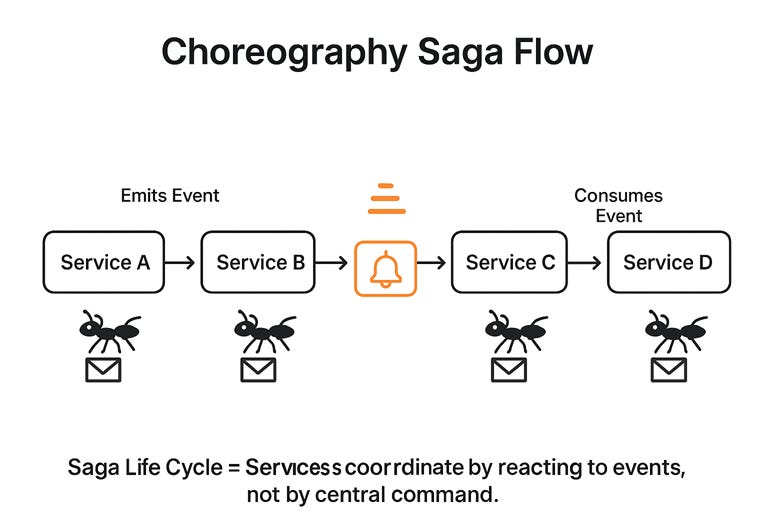

Choreography: The Decentralized, Event-Driven Approach

Event-Driven Flow: Like Ants in a Colony 🐜

In a choreography-based saga, there’s no master conductor. Each service:

Executes its local transaction.

Publishes an event to a broker (Kafka, RabbitMQ, Event Grid, etc.).

Other services listen and react, triggering their own local transactions.

The system moves forward one event at a time, with no central control — much like ants in a colony. Each ant just follows local rules (“if you smell this pheromone, do X”), yet together they achieve complex behavior.

Strengths & Weaknesses

✅ Strengths:

Loose coupling – services know nothing about each other, only about events.

No central SPOF – resilience comes naturally.

Easy to start – great for simple workflows and greenfield projects.

❌ Weaknesses:

Hard to debug – the transaction flow is scattered across services.

Risk of spaghetti events – cyclic dependencies creep in as systems grow.

Distributed error handling – each service must implement its own compensation.

💡 Architect’s Insight:

Use choreography when you’re evolving from a monolith or building a lightweight, event-driven system. But beware — once you have more than ~5–6 services in a saga, debugging becomes a nightmare.

Orchestration: The Centralized, Command-Driven Approach

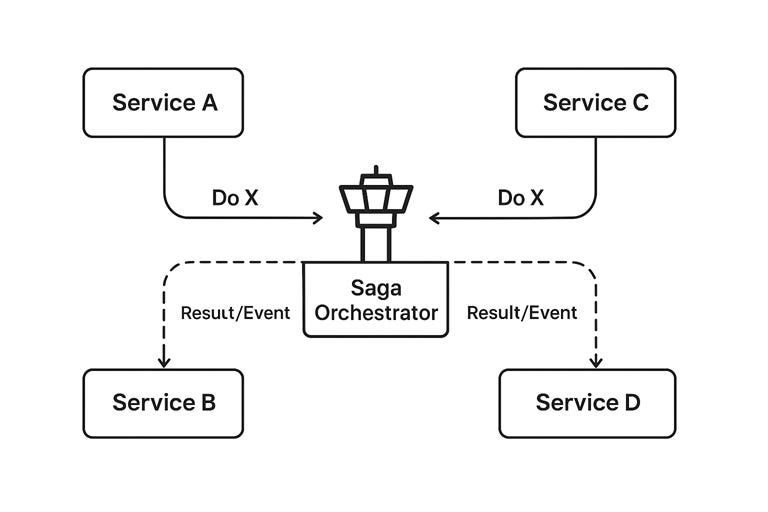

The Orchestrator: Like an Air Traffic Controller ✈️

In orchestration-based sagas, a central orchestrator (sometimes called Saga Execution Coordinator, or SEC) runs the show.

It:

Defines the full workflow.

Sends commands to services (“reserve seat”, “charge card”).

Tracks state and handles compensations.

Think of it like an air traffic control tower. Planes (services) don’t decide when to land or take off; the tower coordinates everything for safety and order.

Strengths & Weaknesses

✅ Strengths:

Clear workflow – everything is explicitly defined in one place.

Simpler services – services just “do what they’re told.”

Centralized error handling – compensation logic is easier to manage.

❌ Weaknesses:

Single point of failure – the orchestrator itself must be made fault-tolerant.

Extra complexity – requires orchestration tooling and operational overhead.

💡 Architect’s Tip:

The SPOF risk isn’t a dealbreaker. Use mature orchestrators like AWS Step Functions, Netflix Conductor, or Azure Durable Functions — they handle retries, logging, and fault tolerance for you.

When to Use What?

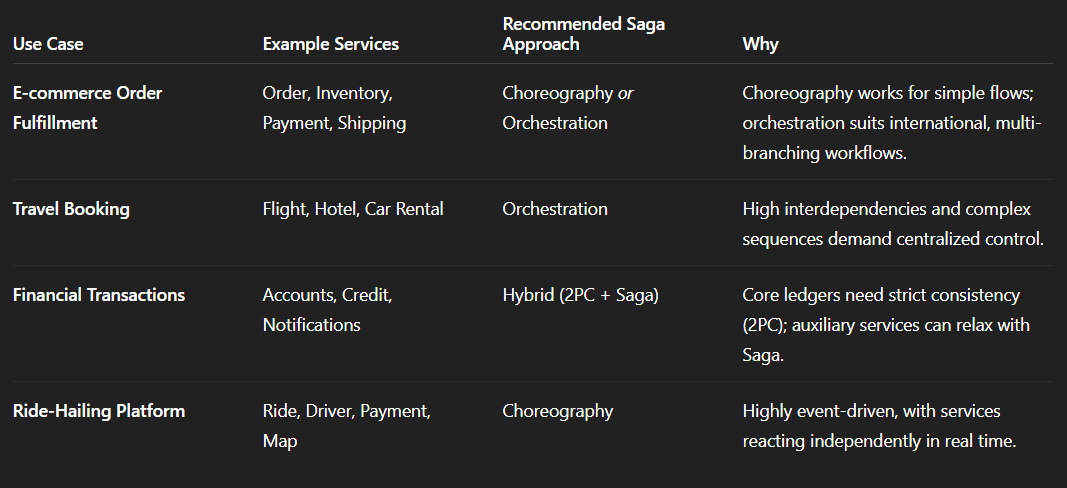

Choreography → Simple workflows, greenfield projects, or event-first architectures.

Orchestration → Complex workflows, strict ordering, brownfield integration of existing services.

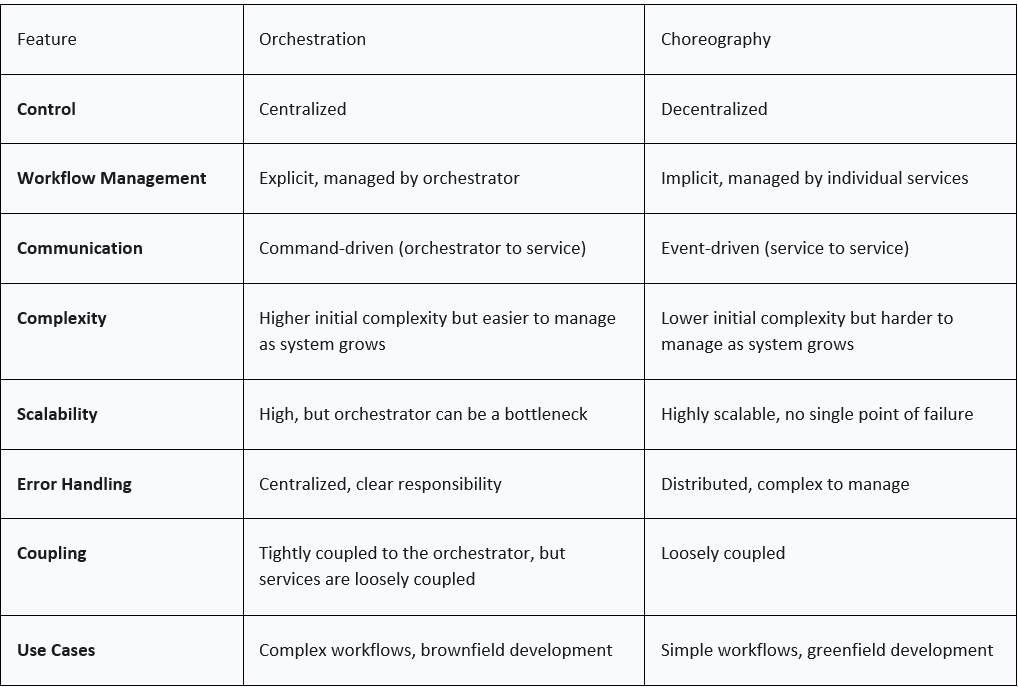

Direct Comparison of Orchestration vs. Choreography

The choice between orchestration and choreography is not arbitrary; it is a fundamental architectural trade-off between decoupling and control. The decentralized nature of choreography promotes high decoupling but leads to implicit workflows that are difficult to trace and debug as the system scales. The explicit control of orchestration, while introducing a central component, provides the clear, declarative workflow that is essential for managing complexity in large-scale systems. The following table summarizes the key differences between the two approaches.

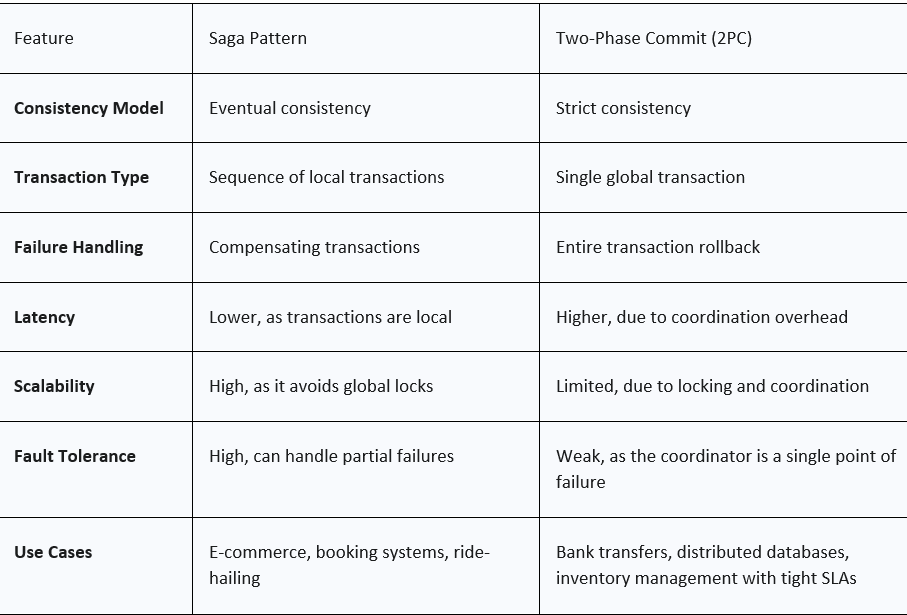

Strategic Decision Matrix: Saga vs. 2PC

The Saga pattern and the 2PC protocol are two distinct solutions to the distributed transaction problem, each with its own set of trade-offs. The decision to use one over the other depends on the business domain’s tolerance for inconsistency. The following table provides a direct comparison.

Real-World Applications and Industry Case Studies

Theory is nice, but sagas earn their stripes in production systems. Let’s look at how real-world giants apply saga patterns — and why their choices differ.

E-commerce Order Fulfillment: The Classic Saga

If you’ve ever bought something online, you’ve (indirectly) seen a saga in action.

Here’s the happy path:

Order Service → creates the order.

Payment Service → charges the card.

Inventory Service → reserves stock.

Shipping Service → books delivery.

Smooth and simple.

But if payment fails? The saga runs compensations:

Cancel the order.

Unreserve stock.

Refund (if needed).

💡 Architect’s Tip:

Start with the order fulfillment example when teaching sagas to teams. It’s intuitive, and almost every developer can map it to their own domain.

Uber Ride-Hailing: Choreography at Scale

Uber’s ride-hailing system is a textbook case for choreography.

The Ride Service emits a

RideRequestedevent.The Driver Service listens, finds a driver, and emits

DriverAssigned.The Ride Service reacts to start the ride.

No central conductor — just services dancing around events.

If something goes wrong (say, no driver found), a compensating transaction cancels the ride request.

Why this works for Uber:

Event-driven by nature → everything is dynamic and real-time.

High autonomy → services must evolve independently across geographies.

Resilience → no single bottleneck controlling the flow.

💡 Developer Insight:

Choreography is best when the business model is naturally event-based and highly dynamic. Perfect for marketplaces, logistics, and IoT systems.

Netflix Conductor: Orchestration Done Right

Netflix took the opposite route. For media processing (like encoding videos into multiple formats), they needed:

Clear, well-defined workflows.

Strict ordering.

Easy monitoring and debugging.

So, they built Conductor — their open-source saga orchestrator.

Uses a JSON DSL to define workflows.

Handles retries, timeouts, and compensations.

Provides a visual UI for tracking long-running workflows.

This central orchestration model ensures observability and reliability, which are critical when you’re dealing with millions of encoding tasks every day.

💡 Architect’s Tip:

Orchestration is the right call when you need clarity, order, and visibility over workflows. Tools like Netflix Conductor, AWS Step Functions, or Azure Durable Functions turn the SPOF risk into a managed service strength.

🌀 Saga Pattern: Strategic Takeaways and Recommendations

Core Takeaways

The Saga pattern is more than just a workaround for distributed transactions — it’s a foundational strategy for building resilient, fault-tolerant, and scalable microservices systems. By embracing eventual consistency, we trade rigid ACID guarantees for flexibility and high availability.

At its core, Saga rests on three pillars:

Local transactions — executed within each service boundary.

Compensating actions — the “undo” logic that keeps the system balanced.

Transaction roles — compensable, pivot, and retryable actions that dictate workflow resilience.

Choosing between choreography and orchestration is less about “right or wrong” and more about aligning with system complexity:

Choreography → great for lightweight, event-driven flows.

Orchestration → necessary when workflows get messy, multi-branching, and business-critical.

Use Case Mapping

Recommendations for Architects & Developers

✅ Know Your Domain

Design decisions should flow directly from business rules. If the process cannot tolerate even temporary inconsistency (e.g., banking ledgers), consider a hybrid model (2PC + Saga).

✅ Plan Ahead

Define local transactions and compensating actions before implementation. Missing rollback logic often leads to cascading failures.

✅ Leverage Frameworks

Don’t build orchestration engines from scratch. Use mature frameworks like Netflix Conductor or cloud-native options like AWS Step Functions to reduce complexity and avoid single points of failure.

✅ Prioritize Observability

Distributed systems fail in surprising ways. Ensure robust logging, tracing, and monitoring so you can track Saga state and debug failures — especially important for choreography.

Final Word

The Saga pattern is not a “plug-and-play” solution — it’s an architectural mindset shift. It asks you to:

Accept eventual consistency as the norm.

Design for failure from the outset.

Balance simplicity with observability.

Handled well, Sagas empower architects to deliver resilient, scalable, and business-aligned distributed systems that meet the demands of today’s digital-first world.

🎙️ Prefer listening over reading?

I’ve also recorded a deep-dive podcast episode breaking down The Saga Pattern: Orchestrating Consistency in Microservices.

👉 Listen to the full episode here

Happy Reading :)